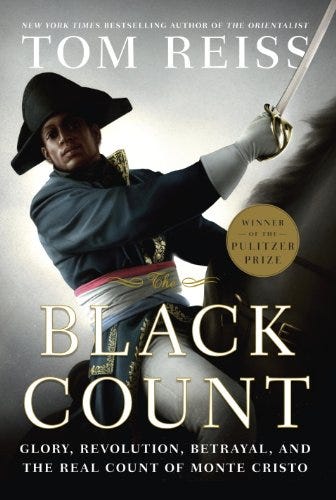

Just finished: The Black Count by Tom Reiss (2013 prize for biography)

Now reading: All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren (1947 prize for fiction)

I.

Over at The Big Read, we’ve been reading Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo all summer, which made Tom Reiss’s The Black Count — a biography of Dumas’s father — an easy pick for the next book in my Pulitzer Project.

Monte Cristo has its moments of greatness, but overall I was honestly a little bit let down. I found the story slow at times, over-plotted, and too long by 500-600 pages.

After reading The Black Count, though, I have a richer and far more appreciative understanding of the son’s famous novel. That’s not to say I necessarily like the story any better, but I get it on a deeper level — which makes a world of difference. Tom Reiss’s superb book was a potent reminder of the power of backstory.

II.

Alexandre Dumas’s father, also named Alex, died when the son was just four years old. Alex, born in what is now Haiti to a white man and a slave, was a general during the French Revolution of the late 18th century. It was a remarkable period of time for the nation, in which slavery was abolished and racial equality was on the horizon.

At one point, though, Alex’s story came to mirror what would later be found in the son’s famous novel. As Tom Reiss writes:

“By the wiles of conspiracy, [Alex Dumas] found himself imprisoned in a fortress and poisoned by unknown enemies, without hope of appeal and forgotten by the world. It was no accident that his fate sounds like that of a young sailor named Edmond Dantes, about to embark on a promising career and marry the woman he loves, who finds himself a pawn in a plot he never imagined, locked away without witnesses or trial in the dungeon of an island fortress called the Château d'If. But unlike the hero of his son's novel The Count of Monte Cristo, Alex Dumas met no benefactor in the dungeon to lead him to escape or to a hidden treasure. He never learned the reason for his trials, for his abrupt descent from glory to suffering.”

Alex suffered a number of ailments and was never the same after his two years in prison. He fathered another child upon returning home — Alexandre — but was soon diagnosed with stomach cancer. In spite of that, Reiss writes:

“Alex Dumas would spend the last four years of his life inseparably attached to little Alexandre.”

After Alex died, the family suffered further indignities by being denied the pension they were owed, plunging them into poverty for the entirety of Alexandre’s childhood.

Reiss notes:

“General Dumas’s son would spend years mulling over his father’s predicament in the Taranto fortress — to be imprisoned indefinitely, for unknown crimes, by men he never met — and reimagining his continual dead-end dialogues with his jailer.”

The seeds of Edmond Dantes are obvious. Whereas Alex Dumas’s untimely death meant he could never get revenge on the men who wronged him, the son’s creation — the Count of Monte Cristo — would be unmatched in dispensing justice.

Writing an all-time classic was Alexandre Dumas’s revenge on behalf of his father. As Reiss wrote, in regards to Dumas’s mindset, “The greatest sin of all . . . was that his father, General Alex Dumas, was forgotten.” With The Count of Monte Cristo, Dumas made sure his father wouldn’t be forgotten, even if disguised in the figure of Edmond Dantes.

Just having that much backstory adds some depth to the novel, doesn’t it? If you imagine Edmond as a superhero version of Dumas’s father, Edmond’s actions make much more sense. Another layer has been added to my understanding of the story and I’m not as annoyed with Dumas as I was before.

III.

It’s almost always the case that when I’ve taken time to get to know the backstory of a book, I appreciate it all the more. Many of my initial harsh judgments become inevitably softened by knowing some of the how and why.

This idea can, of course, be applied much more broadly.

IV.

Beyond the reminder of how important a backstory can be, there was a really interesting lesson in societal progress. For about a decade in the late 1700s, France was more progressive and racially diverse than almost any other nation on earth. Then Napoleon grabbed power and subsequently rolled back those freedoms. There are other moments in history that have taught us this lesson as well — America’s Reconstruction period after the Civil War, for instance — but it’s worth hearing again and again that progress, once achieved, must be fought for on a regular basis.

I really enjoyed The Black Count overall. Even just a handful of days later, it’s feeling rather sticky in my memory. I highly recommend this unique story that combines military history, literary backstory, and cultural treatise on racial equality.

Thanks for reading. I appreciate your time and inbox space.

-Jeremy

Once I finish Monte Christo, I may go back to this biography. Can’t wait to hear your thoughts on All the Kings Men. So good.

I love the back story. And an even further back story to Dumas is his general Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges a fabulous overview: https://www.instagram.com/reel/Ck8vJmOgqkq/?igshid=MzRlODBiNWFlZA==